Lex Rotary keyboard demo with Peter Dyer

We recently met up with Peter Dyer (keyboardist for Mariah Carey, Aloe Blacc, Van Hunt) and he graciously put together a few audio examples featuring

Free US Shipping On Orders Over $49

Easy 30-Day Returns

Financing Available Through ![]()

Jazz greats like Jimmy Smith, Jimmy McGriff, and Shirley Scott used it. Funky and soulful players like Art Neville of The Meters and John Medeski of Medeski Martin & Wood: check. It’s integral to the sound of Gregg Allman’s organ playing, and is an indispensable ingredient in the famous organ solo parts from classic rock tunes like Kansas’s “Carry On Wayward Son” and Yes’s “Roundabout.” While all of these examples use Hammond organs, that’s only half the story. None of them would have their magical sound without rotary speakers. Specifically, Leslie rotary speaker cabinets.

Although originally developed for organ, before long the Leslie rotary speaker was put to other uses. To pick a few examples out of many: Over the years John Lennon ran his vocals though it, and George Harrison and David Gilmour played their guitars through it. Engineer Eddie Kramer ran Jimi Hendrix’s lead guitar parts on “Little Wing” through a rotary speaker cabinet. Joe Walsh used it on guitar, piano, vocals, and organ on the early James Gang albums. In slightly more recent musical history, Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell wrote “Black Hole Sun” while playing a Gretsch guitar through a Leslie speaker, and the rotary speaker sound is one of the trademarks of the production on that song.

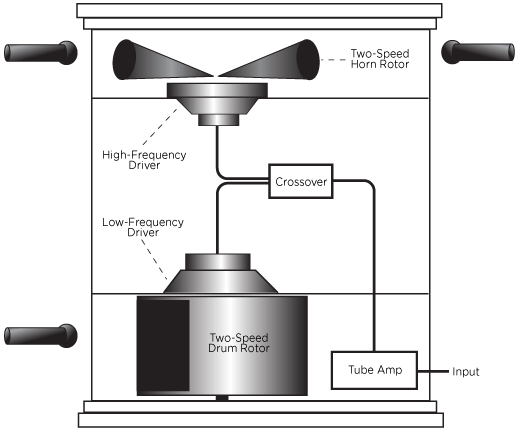

Vintage Leslie speaker cabinets included an internal tube amp which could add some wonderful grit and warmth, and they contained a rotating horn directing sound from a high frequency compression driver, as well as a downward-firing low frequency driver projecting into a rotating cylinder with a rectangular cutout. This produced amplitude modulation/tremolo (raising and lowering of volume) from the bass speaker, and frequency modulation/vibrato (rising and falling of pitch) from the rotating horn due to the Doppler effect (with some amplitude modulation more noticeable when miked close). Close miking using two mics (such as SM57s) to capture the horn and one mic to capture the low frequency driver can capture a nice stereo effect (like on “Little Wing”). Placing the microphone(s) further away results in a smoother and more natural room sound.

The speed of the rotation could be controlled remotely by a switch (found on organs like the Hammond B3) which had three positions: slow (or Chorale), fast (or Tremolo), and Stop. In this mechanical system, it took several seconds for the speed changes to happen completely as motors would spin up or spin down, and there was also a bit of lag when the brake was applied (Stop) or let go. The ability to create these gradual changes in rotation speed became part of the musical expressiveness of playing through a Leslie speaker. For a much deeper exploration of the complex sonic interactions within a rotary speaker system, check out this article by Pete Celi.

“Hey, I have an idea: What if we made an amplified speaker cabinet with a treble horn that spun around really fast, and a bass speaker on top of a cylinder that also spun around really fast?”

If it hadn’t already been done, wouldn’t you think that idea sounded a little crazy? Well, luckily for the countless music fans who love that sound, it didn’t seem prohibitively crazy to Donald Leslie.

Leslie had heard a Hammond organ in a concert hall and had been quite impressed with the sound. However, when he heard the same organ in a small room, he was disappointed in what he heard. Applying some prior experience with electronics to the challenge of making the Hammond organ sound the way he thought it should (even in small spaces) lead to his 1937 invention of what would become his own patented rotary speaker cabinet. In fact, Leslie took his invention to Hammond, and it was promptly rejected. So Leslie started a company and manufactured the speakers on his own. Although the Leslie speakers were at first predominantly used for gospel music in churches, the combination of Hammond organ and Leslie speaker soon found its way into other styles of music as well, and the rest is history.

Leslie speaker cabinets are wonderful. And also large. And heavy. And may require maintenance. And definitely won’t fit in a carry-on bag. Lex provides you with a complete, accurately reproduced rotary system: the low-frequency bass rotor, the rotating treble horn, the tube-driven amplifier, finely tuned microphone placement, and all the complex sonic interactions between these elements.

Lex gives you all the expressiveness of a rotary speaker system. Tap the footswitch to ramp up or down between slow and fast speeds, with all the characteristic sonic richness and complexity during acceleration and deceleration. Hold the footswitch to apply the brake and stop rotation, then take your foot off the switch to accelerate from Stop back up to the currently selected speed. You get controls for mic distance, horn level, preamp drive (for dialing in that signature tube growl), acceleration time, and more. Lex is a stereo pedal, and by default it gives you stereo horn mics and the bass speaker panned center. Or you can use the selectable Bi-Amp mode that splits bass rotor and treble horn signals to separate outputs. You can even change the position of the cabinet relative to the microphones: In the Front orientation the sound travels through the slats in the wood cabinet. In the Rear orientation, the cabinet is open for a different sound.

In addition to offering a Rotary modulation machine, Mobius can produce the sounds of several other effects that have been used to emulate rotary speakers over the years, including Vibe, Chorus, and Phaser. Mobius goes beyond reproducing those lush vintage sounds and allows you to go far out into new sonic territory. With twelve modulation machines, 200 presets, plus MIDI control, Mobius opens up the history books of music while providing new sounds and inspiration for all of your musical ideas.

Subscribe to our newsletter to be the first to hear about new Strymon products, artist features, and behind the scenes content!

We recently met up with Peter Dyer (keyboardist for Mariah Carey, Aloe Blacc, Van Hunt) and he graciously put together a few audio examples featuring

We’re super-excited to announce that Lex Rotary has received Premier Guitar’s coveted Premier Gear award! We’re also extremely proud that it has received 5 out

When we decided to create a studio-class pedal that faithfully recreates the classic, unmistakable sound of the most sought-after rotating speaker system, we prepared to

12 Responses

Brian Auger doesn’t use a Leslie. He uses a direct line out to a Marshall amp.

best!

Mark Trayner

Vintage Hammond Hire (Scotland)

Yes, thank you for catching that. Our author has fixed that 🙂

Was John Lennon the first to run vocals through it?

Great question! We are not 100% sure of the answer. Regarding the use of a Leslie Speaker to process John Lennon’s voice on the song “Tomorrow Never Knows,” a Wikipedia article entitled “Recording practices of the Beatles” states that “Although it’s not the first recorded vocal use of a Leslie speaker, the technique would later be used by the Grateful Dead, Cream, The Moody Blues and others,” citing the book The Foundations of Rock: From “Blue Suede Shoes” to “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” by Walter Everett. If someone has the definitive answer to what was actually the first recorded use of a Leslie speaker on vocals, we’d love to know!

There is no mention of the Wurlitzer Rotating speaker form the 50’s. Yes t was for an organ but it has a tube amp and Alnico speakers!

Thanks for this comment, Jim! Indeed the Wurlitzer Spectratone system is a part of rotary speaker history, as is the Allen Organ Gyrophonic Projector rotating speaker. Both were answers to the Leslie system, and both had different designs than the Leslie to avoid patent infringement. The Spectratone is a pretty cool device! Thanks again for a great contribution to this discussion!

Mid 70’s Mesa Boogie actually produced a spinning speaker. I bought 145s instead. The Mesa stayed way clean for most pop music.

Thanks, James! Great addition to the discussion. The Mesa Revolver has a couple of notable departures from the Leslie in that the Mesa had no rotating treble horn, just a single 12″ driver, and that whole 12″ driver rotates.

In your article you twice mentioned that Leslie speakers incorporate two treble speakers. That is patently false. There is one driver, firing into a rotating horn. One end of the horn is in fact blocked. It is only there as balance. I’m surprised that somebody is knowledgeable as you would make such a rookie mistake.

Thank you very much for this comment, Edwin. I am the one to blame for the error. The article has been corrected. Thanks again.

It’s worth keeping in mind that what a Leslie simulation does is simulating a recorded Leslie. This can work almost to perfection and beyond (there is little point in adding motor noise and wind noise to the emulation). It’s perfect for creating recordings, and it works for large venues where the audience sound is produced by a PA rather than the stage amps (even if the PA reproduces sound miked off the stage amps).

The situation where there is a definite difference is when there is no microphone interspersed between speaker and listener: ears are not mounted on stands and head movements tap into a soundscape that is a lot more complex than stereo channels. Because of the size difference of Leslie speakers and a modern concert PA, this means a “real” Leslie actually can only make a difference for concerts of comparatively modest commercial viability. It’s a sound that does not scale to mainstream success.

And for home practice volumes, the motor (and bearing) noise can be distracting. So the real thing offers real add-on value in limited circumstances and is heavy. Still fun.

Edwin may be correct, that said, his choice of words rang as off-putting with a negative closing statement that I found unnecessary